I hate it when I see someone watching television in the wrong aspect ratio; for some reason it really bugs me.

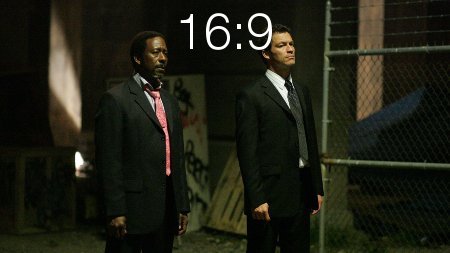

Aspect ratio is always given as horizontal:vertical. Television programmes are usually produced in one of two formats: “regular” 4:3 and “widescreen” 16:9.

If you watch a 4:3 programme with a widescreen television on its 16:9 setting everything looks stretched – people look short and fat.

A widescreen television should be using the 4:3 setting to watch a 4:3 programme. This wastes some screen real estate with black bars at each side of the screen, but it prevents distortion.

Likewise, a 4:3 television should be using the 16:9 setting to watch a 16:9 programme. This creates the familiar “letterboxing” effect at the top and bottom:

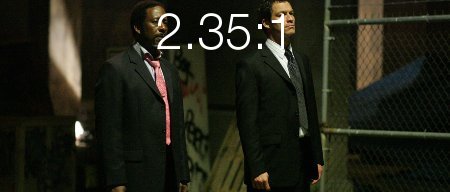

For movies a ratio of 2.35:1 is very common but others are frequently used. Ben Hur was shot in an incredible 2.76:1.

Philips have gone as far to produce a “cinema-ratio” TV: