or Why do screens and monitors use red, green and blue pixels whereas printers use cyan, magenta and yellow ink?

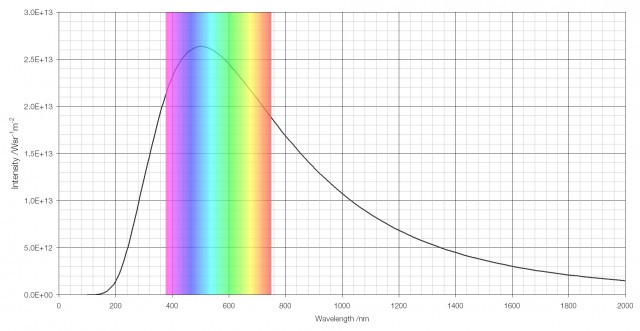

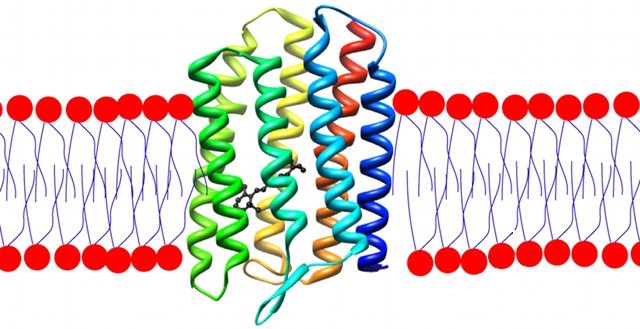

The human eye contains three types of cones, light-sensitive cells that are sensitive to specific wavelengths (rather than rods, which are sensitive only to brightness/darkness).

The sensitivity of the three types of cones peak at wavelengths of 564-580 nanometres, 534-545 nm and 420-440 nm. These correspond to red, green and blue light, and by comparing the signals from the three types of cones the brain creates colours along red-green and blue-yellow axes (hence why there is no such colour as “greenish-red” or “yellowish-blue”). White light is created by the brain when all three cones are stimulated by the same amount.

For a colour to be perceived light must enter the eye. The big difference between the pixels on a computer screen and the inks used in printing is that light from screens enters the eye directly whereas light from printed materials must be reflected first. Screens use additive colour mixing, and printing inks use subtractive colour mixing.

Source: Kodak test image library

To create the test image shown above on a screen, which emits light, the image is split into red, green and blue components. The darker areas are where less light is emitted.

To create this image in print, the image is split into cyan, magenta, yellow and black components (because the mix of cyan, magenta and yellow alone does not produce a perfect “strong” black, and would require the images to be lined-up perfectly). The lighter areas are where less ink is printed.

If both red and green light enter the eye in equal amounts, the brain creates the colour yellow.* To create the colour yellow on the printed page, both red and green light must be reflected from the page, and the only way to do this is to absorb blue. If yellow text is viewed under a blue light it will appear black, as all the light incident on the ink will be absorbed.

| Colour | Additive (Light) | Subtractive (Inks) |

| Red | Emit red | Absorb green and blue |

| Green | Emit green | Absorb red and blue |

| Blue | Emit blue | Absorb red and green |

| Cyan | Emit green and blue | Absorb red |

| Magenta | Emit red and blue | Absorb green |

| Yellow | Emit red and green | Absorb blue |

If cyan and magenta inks are printed on top of each other and illuminated by white light, the cyan will absorb red and the magenta will absorb green. The net effect of this is that only blue light is reflected, so printing cyan and magenta on top of each other creates the perceived colour blue.

If you tried to do this with, for example, red and green ink, the result would be black, as the red would absorb the blue and green and the green would absorb the red and blue. The reason you cannot print using red, green and blue inks is that red, green and blue ink absorbs more than one colour, whereas cyan, magenta and yellow do not. The only way to produce light colours is to start with light inks.

| Ink | Absorbed | Reflected | Colour Perceived |

| Cyan | Red | Green and blue | Cyan |

| Magenta | Green | Red and blue | Magenta |

| Yellow | Blue | Green and red | Yellow |

| Cyan + Magenta | Cyan absorbs red | Blue | Blue |

| Magenta absorbs green | |||

| Magenta + Yellow | Magenta absorbs green | Red | Red |

| Yellow absorbs blue | |||

| Cyan + Yellow | Cyan absorbs red | Green | Green |

| Yellow absorbs blue |

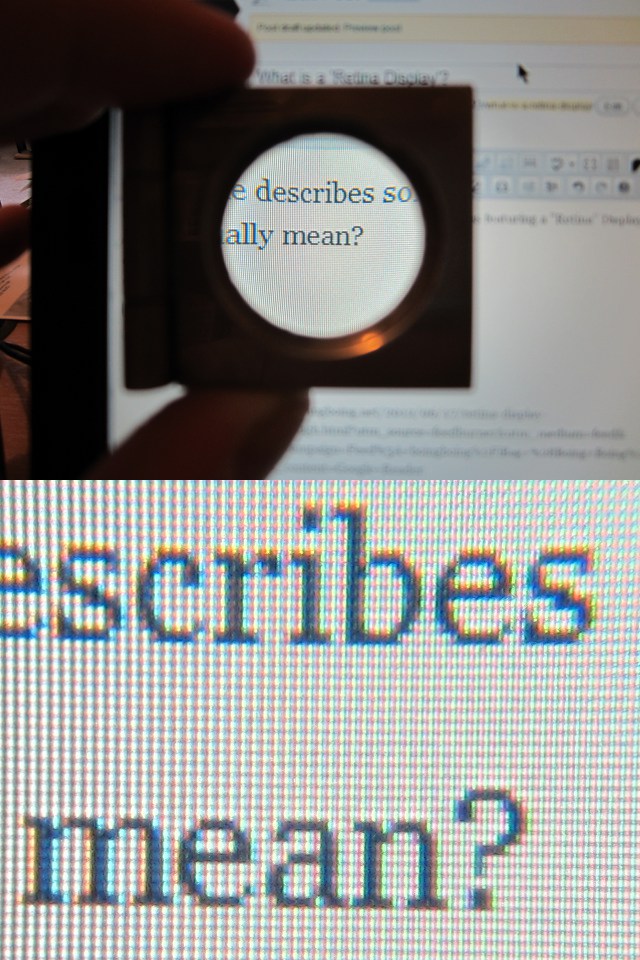

If you’d like proof of the table above, try printing out squares of red, green and blue and looking at them under a microscope.

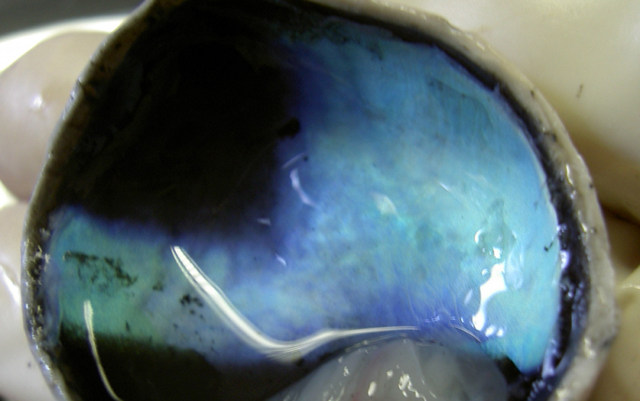

It is easy to see, in the image of blue ink above, the cyan and magenta “pixels” (drops of ink) that create the blue colour. It’s more difficult, but possible, in the image of red ink below to see the magenta and yellow “pixels”.

* There is no way to guarantee that both you and I perceive the colour that we call yellow in the same way. We might both call it yellow, but we could be seeing vastly different things.

I’ll be using this test image of a forest and rainbow throughout.

I’ll be using this test image of a forest and rainbow throughout.