There’s a fascinating paper in this week’s Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America (PNAS) journal about people’s perceptions of the energy used and saved by various devices and methods.

The researchers’ conclusions are not good news, especially in the light of the energy savings that are required to reduce anthropogenic climate change:

“[P]articipants in this study exhibited relatively little knowledge regarding the comparitive energy use and potential savings related to different behaviours … [they] were also … unaware of differences for some large-scale economic activities … and everyday items.”

The researchers recruited 505 volunteers using Craigslist (which must introduce an interesting set of biases) and asked them to estimate the amount of energy used by various household devices, and to estimate the amount of energy saved by various methods.

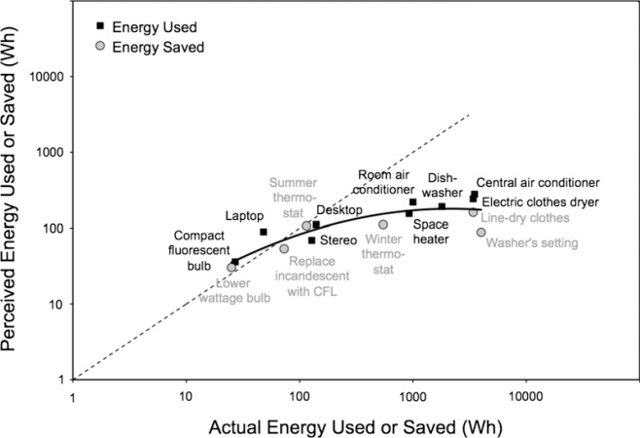

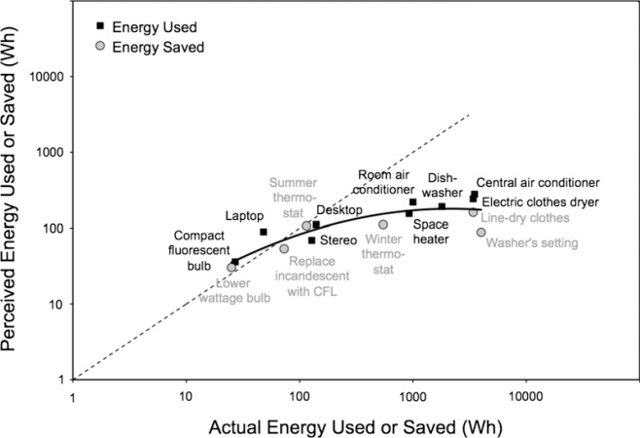

On average the study’s participants underestimated the energy used or saved by a factor of 2.8; people estimate that a device using 1000 watts of electrical power actually only uses 350W and a method that saves 500W would be estimated to save only 180W.

Participants did understand that energy savings were possible, but underestimated the size of the saving. For example, participants knew that a laptop computer used less power than a desktop computer, but thought that the saving was less (23W) than it actually was (92W). The more energy a device/method used or saved, the less accurate participants were. Participants estimated that transporting goods by truck used about the same amount of energy as transporting by train or ship, despite the fact that trucks actually use ten times as much energy: they overestimated the use of energy by ships and trains and underestimated trucks and aeroplanes.

In this graph from the paper overestimates appear above the dashed line and underestimates below.

The activity most commonly selected in answer to a question about the single most effective thing participants could do to save energy was “turn off lights”, whereas in reality resetting the thermostat or washing clothes on a colder setting would save far, far more energy. Far more participants selected “curtailment” activities (e.g. turning off lights, not using the car) as saving more energy than “efficiency” activities (e.g. switching to compact fluorescent lightbulbs) despite the fact that the opposite is most likely correct.*

* See Gardner, G. and Stern, P. (2008) The short list: the most effective actions US households can take to curb climate change, Environment Magazine, 50, pp. 12-24. Link