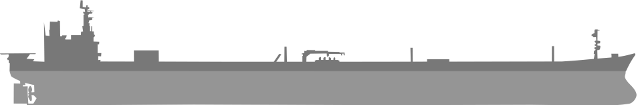

French physicists from the École Polytechnique and the Commissariat à l’Energie Atomique et aux Energies Alternatives have published a paper that looks at the possibility of finding clandestine or rogue nuclear reactors by using mobile neutrino detectors transported by supertankers.

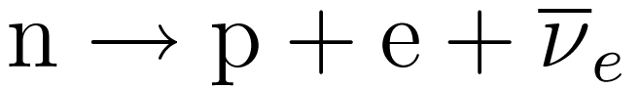

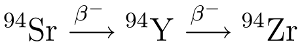

The fission of uranium and plutonium produces fission fragments that have too many neutrons. In order for these radioactive isotopes to become stable they must lose their excess neutrons and they do this by the process of beta decay in which a neutron becomes a proton, with the emission of an electron and an electron antineutrino.

Nuclear reactors are therefore prodigious producers of neutrinos; for every gigawatt of thermal energy generated by a reactor about a thousand million million million electron antineutrinos are produced.

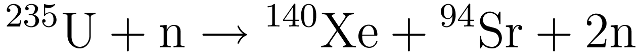

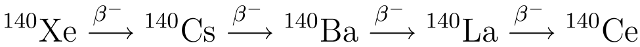

For example: the fission of uranium-235 can produce xenon-140 and strontium-94 fission fragments (along with two neutrons that go on to cause further fissions, thereby continuing the chain reaction):

Both xenon-140 and strontium-94 are neutron rich and must undergo a number of beta decays before they become stable and each of these beta decays results in the emission of an electron antineutrino.

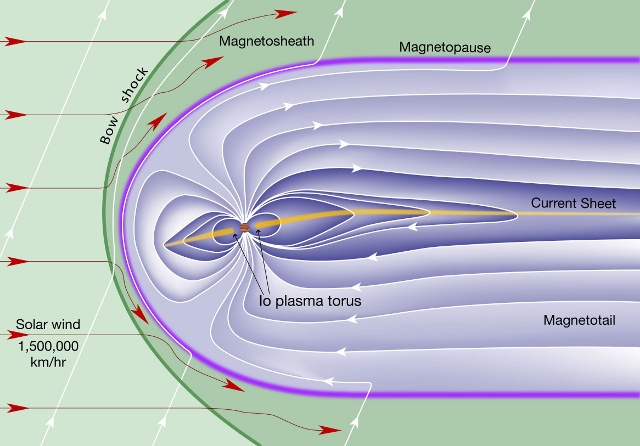

Neutrinos are tiny, almost massless particles that pass through matter without interacting with it (about fifty million solar neutrinos pass through your body every second). Because they don’t interact it is impossible to prevent them from being leaving the reactor and this is what makes their detection an interesting possibility for identifying hidden reactors: burying your reactor a mile underground in a mountain won’t work, a mile of rock is nothing to a neutrino.

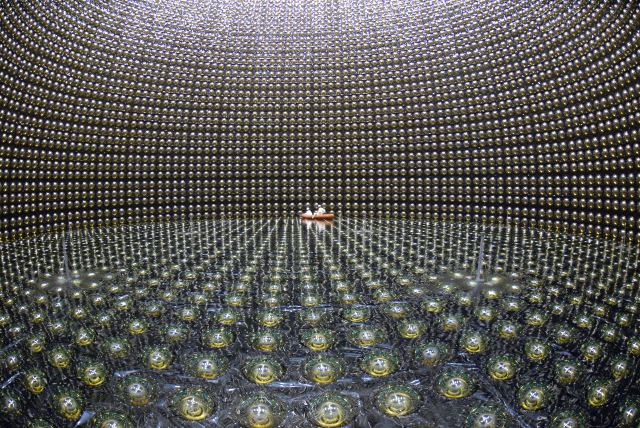

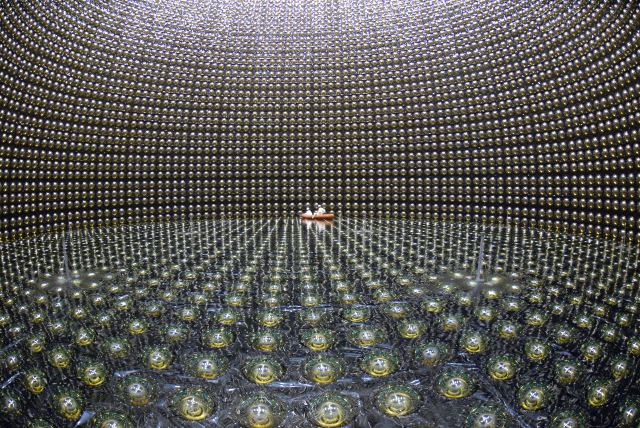

Neutrinos’ weakly interacting nature is a curse as well as a blessing. Neutrino detectors have to be very large so that they have a reasonable chance of capturing a neutrino “event” in a reasonable timeframe. SuperKamiokande, a neutrino detector in Japan containing fifty million kilograms of ultra-pure water in a cylinder 39m across and 41m tall, detects only about fifteen events per day.

Part of the SuperKamiokande detector, with Japanese physicists and rubber dingy for scale.

Part of the SuperKamiokande detector, with Japanese physicists and rubber dingy for scale.

The French physicists’ paper suggest a cylindrical detector 46m across and 95m long which would be transported to its location and submerged two kilometres underwater. The detector would be filled with a hydrocarbon called linear alkylbenzene doped with gadolinium (to increase the detection rate) and surrounded by thousands of photomultiplier tubes that pick up the flashes of UV light caused when a proton in the detector “absorbs” the electron antineutrino. They suggest that they could easily locate a three hundred megawatt research reactor producing fuel for a nuclear weapon to within “a few tens of kilometres” from three hundred kilometres away after only sixth months’ observation.

via The Physics arXiv Blog

A high-gain Yagi-Uda antennae used for terrestrial digital television.

A high-gain Yagi-Uda antennae used for terrestrial digital television.

Part of the SuperKamiokande detector, with Japanese physicists and rubber dingy for scale.

Part of the SuperKamiokande detector, with Japanese physicists and rubber dingy for scale.