One of the most difficult aspects of the Manhattan Project that built the first nuclear bombs was obtaining enough enriched uranium to make the bomb work. The enrichment of uranium took place at a site near the Oak Ridge National Laboratory and used three different methods: electromagnetic separation, gaseous diffusion and thermal diffusion. The gas centrifuge method of separation that is the modern standard could not be made to work at the time.

The final stage of enrichment was the electromagnetic separation stage that took place in a building known as Y-12; the output from the S-50 thermal diffusion plant and the K-25 gaseous diffusion plant (which at the time was housed in the world’s largest building by floor space) was used as input for Y-12.

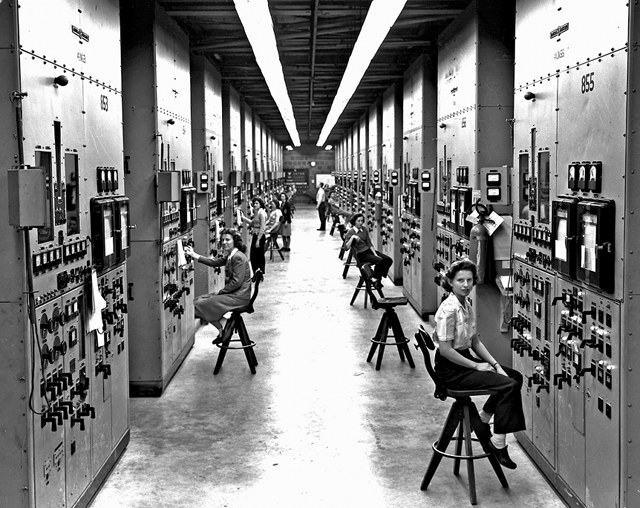

Electromagnetic seperation was carried out on calutrons, which used giant electromagnets made of silver* to deflect the paths of ionised uranium-235 by a little more than ionised uranium-238. Initially these calutrons were operated by scientists from the University of California, Berkeley where the calutron was invented by Ernest Lawrence, but when a reasonable rate of return was achieved the operation of the calutrons was turned over to operators from the Tennessee Eastman Company.

These Tennessee Eastman operators were mostly women and all of them were only educated to high school level.

“The Calutron Girls”

Major General Kenneth Nichols, the man in charge of ore procurement and feed materials, pointed out to Ernest Lawrence that Eastman’s “hillbilly girl” operators were achieving better rates of production that his scientists and engineers had and a competition took place, with Eastman’s operators beating out Lawrence’s scientists. Nichols put this down to the fact that the girls were “trained like soldiers not to reason why … [whilst] the scientists could not refrain from time-consuming investigation of the cause of even minor fluctuations of the dials”.

During the operation of the calutrons the staff from Tennessee Eastman had no idea what they were doing: they operated switches and dials and monitored meters, but had no idea what those switches and dials did or were related to.

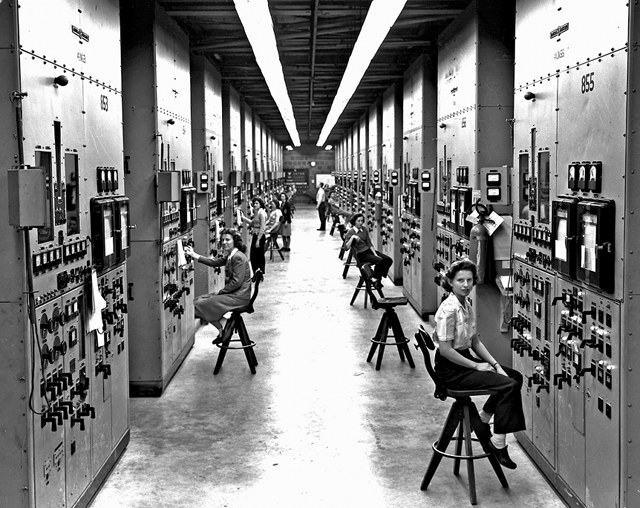

Gladys Owens, seated in the foreground of the photograph above, only discovered what her job was when taking a public tour of the K-12 facility fifty years later. Owens stated that she was told by a manager during a training session “We can train you how to do what is needed, but cannot tell you what you are doing. I can only tell you that if our enemies beat us to it, God have mercy on us!” and said that “Everywhere you looked it told you to keep your mouth shut!”.

Gladys Owens returns to K-12, fifty-nine years later.

* Normally copper would be used to construct electromagnets but this was in short supply due to the war. Kenneth Nichols met with the Under Secretary of the Treasury and arranged to borrow 13 300 tonnes of silver (worth about £170 million at today’s prices) from the US’s West Point Bullion Depository. After the war ended the silver was melted down and returned, with only a tiny fraction being lost in the process.